Betting is about securing positive expected value to make a consistent profit. As part of that process, bettors must consider the influence randomness and luck have on the outcome of any given event. This article looks at whether becoming a profitable bettor is a question of luck or skill. Continue reading to learn more.

The purpose of Squares & Sharps, Suckers & Sharks was to investigate whether and why some bettors are better at making a profit than others. Mirio Mella has previously illustrated how some careers are better suited to becoming successful bettors than others: actuaries, financial traders and professional gamers for example. In this article, however, we will explore more generally whether the ability to succeed in a betting environment is down to luck or is it a skill that can be acquired.

Luck and the Paradox of Skill

Most of what happens in a betting market is chance. This is not something that sports bettors probably wish to hear. Sure, casino games like roulette and craps are pure games of chance, governed by simple rules of probability. But sports where the probabilities of outcomes are essentially unknown, surely that must offer an opportunity for profitable expectation, right? Yes, technically it does, since it’s possible for some to be better at accessing and processing news and information than others, but in practice it’s really only available for a small proportion of players because of an effect known as the paradox of skill.

Generally speaking the lower scoring the sport and the greater the number of players participating, the greater the role of luck.

When the business of forecasting becomes an arms race between players using ever more sophisticated methods for predicting a sporting outcome, absolute skills may very well improve across the board, but relatively speaking we largely stand still.

Whilst absolute forecasting skills improve, the difference between the best and worst narrows; since betting is a game of skill and luck, if the variance in relative skills has shrunk, consequently the influence of luck is greater. Once you factor in the cost of playing (the bookmaker’s margin) most of us will likely end up in the red in the long run.

Betting robots vs. Chance

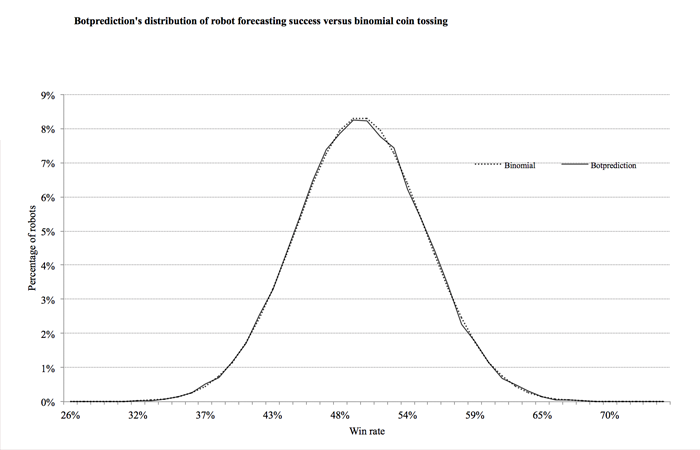

The football prediction service Botprediction.com offers a useful means of demonstrating the randomness in betting. Simultaneously running 40,000 soccer prediction robots for the total goals betting market, Botprediction likens them to a large group of gamblers.

“Statistically, there are always big losers and big winners in that group. Our prediction software enables you to follow those few winners with win rates above 70%”

A couple of years ago I decided to analyse the distribution of performances of these robots over a 5-week period. This is what it looked like.

Essentially there was no difference between what the robots were doing and a random coin toss. The idea that you could choose to follow one of the better performing robots and expect it to continue to perform in the same way is complete nonsense. There is no consistency whatsoever between the performance over one 5-week period and the next. Robot success rates simply regress to the mean. Everything that happens is pure chance.

Real people vs. Chance

Of course, if robots are just randomly picking outcomes to bet on then we can hardly be surprised by this finding. Let’s replace the robots with people. Surely there must be a difference since people don’t pick randomly.

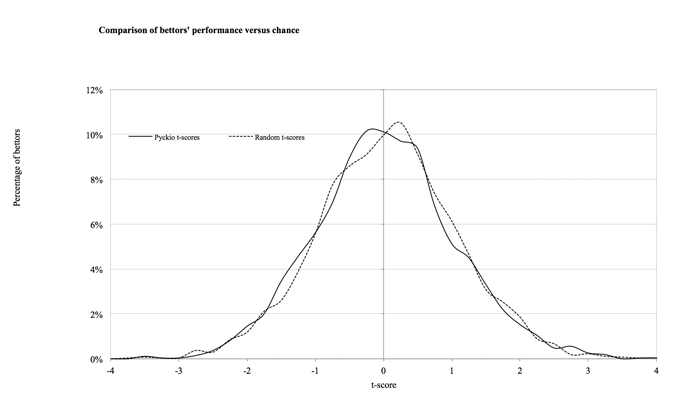

In addition above analysis, I also analysed a large sample of bettors (6,044) posting picks (1,073,029 in total) on the sports betting community Pyckio.com. Analysing performance using the t-score, a statistical measure of how a betting record compares to market expectation based on Pinnacle’s odds, this is how their performances were distributed.

We see a normal distribution in betting performances, a sure sign that what you’re looking at is mostly random. Yes, there are good bettors and bad bettors, but their distribution closely resembles what we would find if we simply had them tossing coins to decide what they were going to bet on; even though each would all tell you how sophisticated their forecasting approach is.

A skilled but unlucky poker player could still be showing losses after as many as 100,000 hands, equivalent to almost two years playing 40 hours per week.

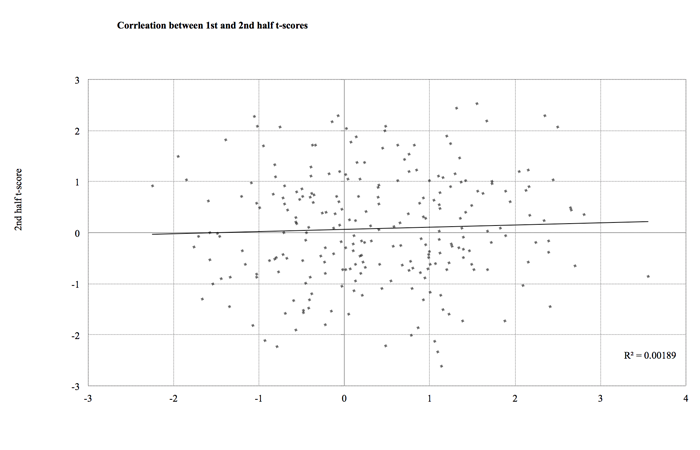

Rather than being good or bad, most of the bettors analysed are merely lucky or unlucky. As a further demonstration, I divided the records of the 249 bettors with histories longer than 1,000 picks into two halves and correlated their performances in the first half with the second.

If bettors were demonstrating evidence of skill beyond luck, performances should typically remain consistent. That is to say, if a skilled bettor shows a t-score of 3 on his first 500 bets, we should typically expect him to show something like 3 for his next 500 bets. This is how those correlations looked in a scatter plot.

An R2 of 0.0019 means that just 0.19% of the variation in the second half performance of these 249 bettors could be explained by the variation in the first half performance. The implication is that all the rest is explained by chance. Collectively, these bettors were not demonstrating consistent performances; like Botprediction’s robot they were largely just regressing to the mean. This is not to argue that there were no skilled bettors at all; rather, what few there might have been were hidden amongst the noise of chance.

The Luck-skill continuum

In his book The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing, Michael Mauboussin defines a luck-skill continuum on which sits various activities. At the extreme luck end, we find things like roulette and lotteries. At the other end are games of pure skill like chess. Most team sports are found somewhere in the middle.

This strongly indicates that the environment within which sports bettors operate is neither regular nor predictable.

Generally speaking the lower scoring the sport and the greater the number of players participating, the greater the role of luck. What about gambling? Mauboussin places things like investing, betting and poker much closer to the luck end than the skill end. The distribution of bettors’ performances shown above would seem to support his decision.

The environment of skill

Typically the acquisition of expertise or skill follows what is termed as ‘Naturalistic Decision Making’, where chunks or patterns of data are memorised and recalled periodically through prolonged practice and feedback. For this to be effective, the environment should be sufficiently regular and stable to be predictable, allowing cause and effect to be meaningfully connected. Clearly such an environment of skill exists for things like learning to play chess or tennis. Can the same be said for sports betting?

When competing in an environment where luck dominates you should focus on the process of how you make your decisions, rather than the outcomes themselves.

The problem of acquiring skills in forecasting lies in the fact that in betting we are not necessarily rewarded for doing so. It may be true that the more time and effort I devote to forecasting sporting outcomes the better I will get at it. But skill in sports betting is not simply a matter of picking winners; rather, it’s about whether we’re better at picking them than everyone else.

As the paradox of skill illustrates, betting amounts to a zero-sum, relative-skills competition. When bettors are competing with each other in a market, the skill that really matters is evaluating whether the available information in the market is already incorporated into the odds, and being able to do that consistently.

If equally skilled players have pushed the odds to a price that genuinely represents the ‘true’ probabilities of a result (a process known as ‘price discovery’), whether one wins or loses is then simply a matter of chance. If betting markets are mostly efficient, that is to say reflecting the ‘true’ result probabilities, the prospects for outperforming this wisdom of the crowdappears to be severely restricted.

A zero-validity environment?

Validity is a measure of whether what we think is the cause is actually the true cause, and whether our measurement repeatedly points to that conclusion. Collectively, the sports bettors analysed earlier failed basic tests of consistency and validity. This strongly indicates that the environment – the betting market – within which sports bettors operate is neither regular nor predictable, but instead dominated by luck.

Where a lot of luck breaks the link between skills (causes) and profits (effects), a skilful player can lose money whilst an unskilled player (relatively speaking) can profit.

The betting market is complex and mostly random because the news that drives the movement of odds arrives tothe market randomly. If it wasn’t random then it wouldn’t be news. Such randomness breaks the link between cause (something the bettor does to bring about an increase in his bankroll) and effect (an actual increase in the bettor’s bankroll).

The corollary between the above is that there is limited scope for feedback. Since feedback is the oil that drives the machinery of deliberate practice, accumulating playing experience in a betting market will be unlikely to deliver much expertise - to put this into perspective, imagine trying to practice a game of roulette.

Similarly in betting the price discovery process that is implicit in the balancing of opinions about a sporting outcome, necessarily means that establishing causal relationships between decisions and outcomes is more akin to guesswork. Daniel Kahneman, Nobel prize winner and author of Thinking, Fast & Slow describes this as a zero validity environment. Of course, none of this alters the perception of most bettors that the profits they experience were caused by things that they did. Such overconfidence (one of the many reasons for why we gamble) is manifestly the product of an illusion of validity.

When does betting become a game of skill?

Perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong question. Maybe it’s not a question of whether something is a game of skill but rather when it becomes a game of skill. Where luck and skill are both present in games involving repetition, the relative contribution of skill increases with the number of repetitions.

Tennis is an obvious example of a game with many repetitions. A 53% probability of winning a single point translates into an 85% probability of winning a 5-set match. Poker is another. The cards you are dealt and the community cards the dealer reveals are purely a matter of chance and are arguably the dominant factors dictating the evolution of play in a single hand. Over many hands, however, good and bad luck cancel out, but differences in players’ ability to bluff and read opponents – a skill acquired through repeated play – will gradually show through.

I might be able to predict 9 out of 10 Premiership results at a weekend but if the person I’m betting against can do all 10, I’ll still lose.

Nate Silver, author of The Signal and the Noise, has suggested that a skilled but unlucky poker player could still be showing losses after as many as 100,000 hands, equivalent to almost two years playing 40 hours per week. Imagine two sports bettors betting even-money propositions against each other. If one has a 2% advantage over his opponent, that is to say a 51% forecasting success rate, the evolution of success through his real advantage could similarly take a long time. After 1,000 wagers the weaker player could still be ahead 25% of the time.

Overcoming chance and the Paradox of Skill

If betting markets are close to being zero-validity environments where opportunities for skill are minimal, is there anything we can do about it? I have added my own solution to the three offered up by Michael Mauboussin, all of which are outlined below:

Bet in markets with a higher variance of skill

In layman’s terms that means betting markets that are less familiar to the majority of players and the bookmaker too, with less readily available information and news to process for forecasting. The bigger the difference between the least and most skilled forecasters, the smaller the role of luck.

Think relative, not absolute

Where there is competition and luck, it’s only relative performance that matters. I might be able to predict 9 out of 10 Premiership results at a weekend but if the person I’m betting against can do all 10, I’ll still lose. As Nate Silver says of poker, “you can make 95% of your decisions correctly and still lose your shirt at a table full of players who are making the right move 99% of the time.” In this context, it’s also important to remember that it’s not really the bookmaker you’re trying to beat, but everyone else.

Focus on the process, not the outcome

When competing in an environment where luck dominates you should focus on the process of how you make your decisions, rather than the outcomes themselves. In betting, analyse the way you forecast, not the size of your bank balance. Where a lot of luck breaks the link between skills (causes) and profits (effects), a skilful player can lose money whilst an unskilled player (relatively speaking) can profit.

Study the closing line

It is now well established that Pinnacle’s closing line provides one of the best measures of ‘true’ result probability. The amount you consistently beat it by will provide a very good indication of the profit you can expect to make. Consistently beating the closing line by an amount greater than Pinnacle’s margin implies that you are sufficiently more skilled than many of your competitors.

MORE: TOP 100 Online Bookmakers >>>

MORE: TOP 20 Bookmakers that accept U.S. players >>>

MORE: TOP 20 Bookmakers that accept Cryptocurrency >>>

Source: pinnacle.com